The management of child singer Gandhi Sehat has proactively removed the album Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi) (My Dream (Not Becoming a Police Officer)) from all music streaming services. They assert that this decision was made voluntarily to prevent misunderstandings.

Adrianus Meliala, a Professor of Criminology at the University of Indonesia, interprets this move as a form of self-censorship. He describes it as an act of restraint undertaken to avoid negative consequences such as intimidation.

“Even though this song is sung by a child, its lyrics are very simple, typical of children’s songs. But the current climate is sensitive and easily offended. Anything is quickly labeled as insult, hatred, and some even lead to terror. That’s why many choose self-censorship,” Adrianus stated on Sunday (15/02).

Police observer Poengky Indarti expressed hope that the withdrawal of the work was not influenced by intimidation. She underscored that music is a vital form of freedom of expression.

“Don’t be afraid to voice criticism, including towards the National Police institution (Polri). The National Police Chief (Kapolri) has repeatedly conveyed to the public that Polri is not anti-criticism and has asked all police members to accept criticism as an effort for improvement,” Poengky remarked.

Chairul Huda, a Criminal Law Expert Advisor to the National Police Chief, affirmed that the album titled Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi) falls within the permissible bounds of artistic creativity.

“I believe Iwan Fals’ songs in the past were social critiques. There was no issue then, let alone now. So if someone creates a song like Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi) or Bayar, Bayar, Bayar (Pay, Pay, Pay), that’s criticism for the police,” Chairul commented.

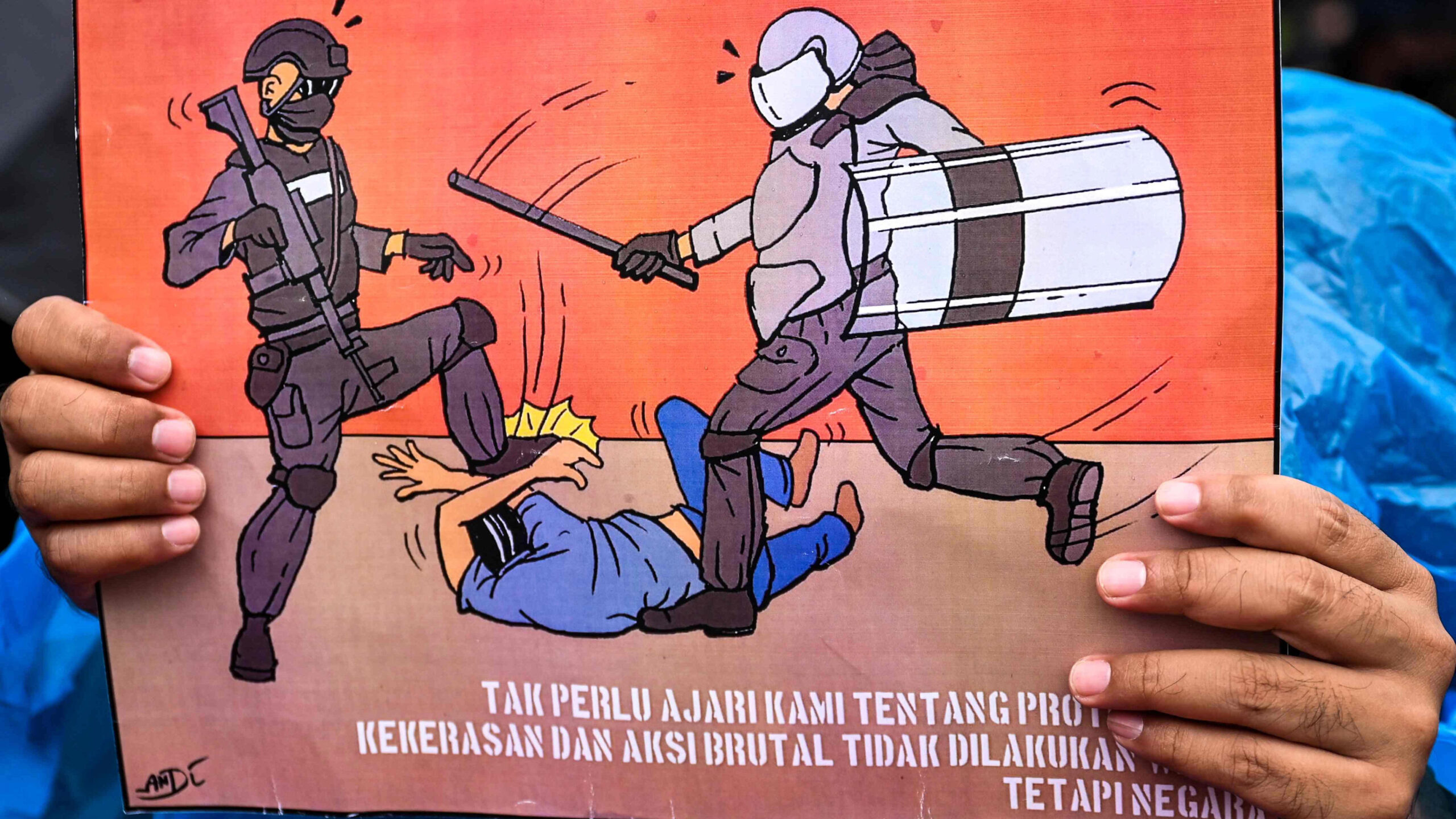

Previously, the punk rock band Sukatani also released a song containing criticism of the police. Following the song’s release, Sukatani reported experiencing intimidation.

This situation raises a pertinent question: What is the significance of the emergence of such critical songs amid survey results indicating an increase in public satisfaction with the police force?

What is known so far about ‘Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi)’?

Gandhi Sehat’s management released the song ‘Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi)’ on February 5th across digital music streaming platforms including YouTube and Spotify.

As of Sunday (15/02), the song had garnered over 46,000 views.

This punk rock-infused track is performed by a six-year-old child from Sleman, Yogyakarta. A snippet of the lyrics includes:

Grandma asks my dream (As long as it’s not becoming a police officer)

Grandpa asks my dream (As long as it’s not becoming a police officer)

Teacher asks my dream (As long as it’s not becoming a police officer)

They ask my dream (As long as it’s not becoming a police officer)

It’s embarrassing, they say

But why can’t I become a police officer?

Well, it’s about that. What’s it called. That thing.

Oh, how to explain. Oh, dad will get arrested later. Just can’t, period.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DUrlVW9k0E3/

A week after its release, Gandhi Sehat’s management decided to withdraw the song from circulation.

When asked for the reason via Instagram, the Gandhi Sehat admin team responded, “Please quote as we have posted, sir.”

“The team decided to take down the song from DSPs last Friday. It will take 3-5 days for the song to disappear.”

In a statement on the Gandhi_sehat Instagram account, the management clarified that the album was initially created as an artistic work, based on the innocent perspective of a six-year-old child.

“However, after observing the evolving dynamics and various interpretations in the public sphere, we decided to cease its circulation. We have now removed all related content and songs from our official accounts and channels.”

“This decision was made without coercion from any party, as a form of our responsibility as creators, and to avoid any unintended misunderstandings,” Gandhi Sehat’s management wrote.

The management also stated that any re-dissemination of content or songs still circulating outside Gandhi Sehat’s official channels is no longer their responsibility.

What is the significance behind this withdrawal?

According to Adrianus Melilala, a criminologist from the University of Indonesia, the action taken by Gandhi Sehat’s management falls under self-censorship.

“These songs are harmless, especially when sung by a child, and the lyrics are very simple, typical of children. But we are talking about its viral nature and sensitivity, which ultimately led to the decision to take down the song to prevent the issue from escalating,” Adrianus explained.

Adrianus clarified that self-censorship is a passive act of withholding or concealing opinions, information, or creative works due to fear, social pressure, or to avoid negative consequences such as intimidation, persecution, or even cancel culture.

Why has self-censorship become a prevalent choice in Indonesia today? Adrianus attributes this to the current sensitive atmosphere where criticism from the public towards government institutions, officials, or policies is easily met with a “short fuse.”

“Because now, criticism is easily interpreted as insult, hatred, and dislike. And even when there is criticism, it is interpreted with acts of terror, such as sending buffalo heads, and so on. This terror is a symbolic step, indicating ‘do not criticize’,” Adrianus elaborated.

Songs, a form of freedom of expression

Police observer Poengky expressed uncertainty regarding Gandhi Sehat’s management’s reason for withdrawing the album Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi). Poengky questioned whether the decision was a market response, a reaction to intimidation, or a form of self-censorship.

“However, fundamentally, it is deeply regrettable if freedom of expression is stifled by fear due to certain powerful parties allegedly feeling displeased. After all, a song is a form of freedom of expression,” Poengky asserted.

She believes that songs cannot be forced to align with everyone’s tastes. Poengky noted that sometimes songs represent social conditions and public criticism, citing ballad songs and even dangdut tracks that depict the socio-economic situation of society.

You might also be interested in:

- Film agency signs cooperation with police, human resource development or ‘oversight’?

- ITB student who made ‘kissing’ Prabowo-Jokowi meme becomes a suspect – ‘Criticism should not be seen as personal hatred’

- Stories of firefighters helping domestic violence victims and theft cases – Why do people prefer reporting to firefighters rather than the police?

Poengky highlighted that during the New Order era, Iwan Fals’ songs were trailblazers, daring to critique the policies of the ruling regime.

“I hope that in this era, people are not afraid to speak up. Don’t be afraid to express criticism, including towards the National Police institution,” Poengky urged.

“The National Police Chief has repeatedly conveyed to the public that Polri is not anti-criticism and has asked all police members to accept criticism as an effort for improvement,” she added.

“The National Police Chief even stated that whoever criticizes the hardest will become a ‘Friend of the National Police Chief’. This must be taken seriously and implemented well by all members,” said Poengky, who served as a Kompolnas Commissioner for the 2016-2024 period.

Poengky emphasized that freedom of expression and opinion is a fundamental human right that must be respected by all parties.

“I hope that cases like those involving the band Sukatani and Gandhi Sehat will not recur,” she stated.

Echoing this sentiment, Kompolnas Commissioner Choirul Anam stated that criticism and self-criticism are normal aspects of any civilization.

“Criticism and self-criticism should be the healthiest pills for our civilization. Therefore, all parties must respect criticism and self-criticism,” he remarked.

Choirul also affirmed that criticism conveyed through artistic media is an integral part of freedom of speech and expression.

“We must collectively respect the boundaries of freedom of expression. In the context of human rights, for example, it means not spreading racial superiority, discrimination, hate propaganda, or violence. Those are the only boundaries that must be respected,” he explained.

Have there been previous artistic works that offered criticism?

Expressing disappointment towards Polri through artistic works is not an unprecedented phenomenon.

Previously, the band Sukatani, a punk music duo from Purbalingga, Central Java, released a song titled Bayar, Bayar, Bayar (Pay, Pay, Pay).

A segment of its lyrics states:

Want to corrupt, pay the police. Want to evict homes, pay the police.

Want to clear forests, pay the police. Want to become a police officer, pay the police.

Oh dear, oh dear, I have no money. To be able to pay the police.

This song vividly portrays an individual’s perpetual experience of having to pay when dealing with the police, thereby fostering a negative perception of the police force’s image.

Following the release of this song, Sukatani reported experiencing intimidation.

Ultimately, Sukatani announced the withdrawal of the song Bayar, Bayar, Bayar from all music streaming platforms. They also issued an apology to the National Police Chief and the institution of Polri.

However, National Police Chief General Listyo Sigit Prabowo claimed that Polri had no issue with the song Bayar, Bayar, Bayar.

“Polri is not anti-criticism. Criticism serves as input for evaluation. In accepting criticism, we must certainly be open-minded, and the important thing is improvement. And if there are things that are not in line with what can be conveyed, explanations can be provided,” Listyo stated.

Prior to this, artist Butet Kartaredjasa alleged intimidation during his theater performance titled “Musuh Bebuyutan” (Arch-Enemy) at Taman Ismail Marzuki in December 2023.

And in 2021, a mural depicting what was believed to be Joko Widodo’s face with red blindfolded eyes and the words “404: Not Found” was vandalized by a group of individuals. A similar incident also occurred in Pasuruan Regency, East Java.

Why do people criticize the police?

Ricardi Adnan, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Indonesia, views criticism expressed through songs as a manifestation of the public’s deep trust and affection for the police.

“From a social psychology perspective, a very deep sense of love, when accumulated with disappointment, can lead to a ‘sense of hatred,’ especially among young people who remain highly idealistic,” Ricardi explained.

“Cases involving rogue police officers in recent years have been numerous enough to injure the sense of justice and cause deep disappointment. For instance, cases of drug offenses, murder, wrongful arrests, and others,” he elaborated.

Art, he noted, is one of the most frequently used channels for expressing emotions, from affection, longing, and love to hatred.

“For socio-political critiques, we are familiar with various works from Iwan Fals, Slank, and others. Naturally, the expressions of frustration within society must become valuable input for the police institution,” he commented.

Ricardi acknowledged that Polri has undertaken reform efforts, such as upholding fair law and protecting the community, although these measures have not yet fully dispelled existing disappointments.

A Litbang Kompas survey in October 2025 revealed that public satisfaction with Polri increased by 22.6% to 65.1%, compared to September 2025.

From the same survey results, Polri’s positive image also saw an increase from 44.5% to 64.4%.

Furthermore, the national survey by Rumah Politik Indonesia (RPI) indicated that public satisfaction with Polri’s performance reached 79.8%. This positions Polri as the law enforcement agency with the best performance based on public assessment.

In The Global Safety Report released by Gallup in 2025, Indonesia scored 89 on the Law and Order Index, placing it 19th out of 144 countries.

How has Polri responded?

Chairul Huda, Criminal Law Expert Advisor to the National Police Chief, reiterated that the album Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi) is a legitimate part of artistic creativity.

“Of course, it’s allowed. I believe Iwan Fals’ songs were filled with social criticism back then. There was no problem, especially now. So if someone creates a song about not wanting to be a police officer or Bayar, Bayar, Bayar, it is indeed criticism for the police. But that doesn’t mean it represents the general perception of the police, does it?” Chairul clarified.

Chairul noted that police officers have duties that directly interact with the community. Therefore, he stated it’s very natural for some members of the public to feel satisfied and others dissatisfied with police performance.

“Our country is a democracy, and thus no state institution, including the police, should be anti-criticism. Criticism is something we desperately need for internal correction, for example, within the police force,” he emphasized.

However, Chairul stressed that criticism must adhere to established legal norms, ensuring it contains no insults or hate speech.

“If the public wishes to offer criticism, they are welcome to do so, and it is certainly very beneficial. But remember that every freedom has its limits, which is responsibility under the law,” he stated.

- Citizens preventing brawls sentenced to prison – What are the limits of self-defense and vigilantism?

- Placement of police under a ministry rejected by National Police Chief, why is this idea not considered a solution?

- DPR Protest: Police vehicle runs over online motorcycle taxi driver to death, Palace apologizes and seven police officers investigated

- Controversy surrounding Sukatani band’s song ‘Bayar, Bayar, Bayar’ – Is this the end of ‘silencing’ criticism against the police?

- Why did the punk band Sukatani’s song ‘Bayar Bayar Bayar’ become the theme song for the ‘Indonesia Dark’ protest?

- Constitutional Court prohibits active police from holding civilian positions – What are the impacts of this decision?

- At least 100 lives allegedly lost at the hands of police in the last three years – ‘They are not just numbers, but human lives’

- Tracing the footsteps of feudalism in Indonesia – From the Mataram Kingdom era to the Prabowo administration

Summary

The management of child singer Gandhi Sehat voluntarily withdrew the album “Cita-citaku (Ga Jadi Polisi)” from streaming platforms, stating the decision was made to prevent misunderstandings. Criminologist Adrianus Meliala interpreted this action as self-censorship, an act of restraint in a sensitive public climate to avoid negative consequences. Police observer Poengky Indarti hoped the withdrawal was not influenced by intimidation, emphasizing music as a vital form of freedom of expression. Criminal Law Expert Chairul Huda also affirmed the album’s place within artistic creativity.

This situation highlights a broader trend of self-censorship in Indonesia, where public criticism towards institutions can easily be misinterpreted. Similar past incidents include the punk band Sukatani’s withdrawal of their song “Bayar, Bayar, Bayar” after experiencing alleged intimidation, despite police statements about being open to criticism. Experts argue that while criticism is crucial for institutional improvement, fears of repercussions can suppress artistic expression and public discourse.